|

|

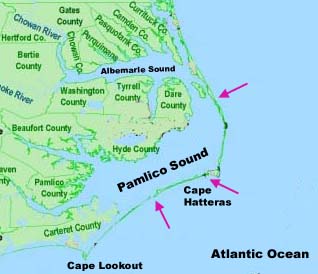

Female blue crabs mate only once in their lives, when they become sexually mature. They capture and store the males' sperm in sac-like receptacles to be used to fertilize their eggs between two to nine months after mating. Soon after mating, the female crabs migrate to high salinity waters near inlets (Figure 1).

At these more saline locations, the females fertilize and spawn their eggs into a large, cohesive mass, i.e. sponge (Figure 2). The sponge remains attached to fine hairs beneath their abdomen until the eggs hatch. The sponge can contain between 750,000 to eight million eggs, depending on the size of the female. Two million is the average. Figure 3 shows the life stages the blue crab from egg to adult.

(www.blue-crab.org/lifecycle1.htm; Etherington & Eggleston, 2000).

|

|

|

||||

In North Carolina, there are two recruitments of juveniles, one minor peak in May and a second larger peak from August to November. Recruitment refers to the life stage when the megalopae metamorphose into the first juvenile stage, and then settles on to the estuary floor. The shallower, less saline waters further up the estuary provide a safe refuge for the juvenile to grow and mature.

However, the molting and growing stops during winter, and resumes as the water warms. The juveniles usually reach maturity during the spring or summer of the year following their hatching. In addition, the blue crab's diet changes as it transitions through its various life stages.

(www.blue-crab.org/lifecycle1.htm; Etherington & Eggleston, 2000).

|

||||||||||||

Blue crabs in North Carolina spend different parts of their lives in various regions of the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine Ecosystem (APEE).

EGGS remain attached to the abdomen of the females, who stay near the inlets, until they are hatched.

LARVAE are transported out of the estuary, and remain in water along the continental shelf.

POST-LARVAE are brought back into the estuary via tidal currents and settle on seagrass. Tropical storms can also carry post-larvae into the estuary, in which case the larvae also settle on submersed rooted vasculars.

JUVENILES migrate from the outer edges of the sound towards the upper estuary and rivers. These regions are less saline, and provide shelter from predators.

ADULTS primarily remain on the estuary floor, and move out towards deeper waters in the middle of the sound. Females remain near the inlets after they mate.

- How would increased rain and flooding affect the blue crabs?

- What ecological disturbances could give rise to increased rain and flooding?

(Eggleston, personal communication 8/14/03)

|

|

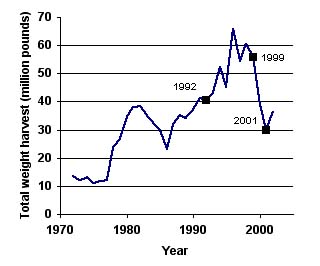

Use this graph of total blue crab landings as an indication of the blue crab population in North Carolina. There was continued increase in blue crab harvest from 1972-1998. Notice the sudden drop in population in 1999-2000.

- What could have caused the sudden drop?

- Is this decline a natural population fluctuation or an indication of overfishing?

- Does the steady increase in blue crab landings from 1972 to 1998 suggest that the blue crab population had been increasing during that time period? Compare this with catch per unit effort data.

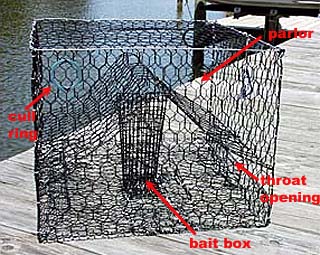

Many types of harvesting gear have been used by the commercial blue crab fishery, including trotlines, crab pots, and trawls. Currently, crab pots (Figure 5) are used in harvesting approximately 95% of total hard blue crabs in North Carolina. The huge jump from 30% crab pots used in the 1950s show that crab pots are more efficient and effective, and thus preferred method for the commercial fishery.

The pots are baited, left in the water, and then harvested at different time intervals. NC Division of Marine Fisheries estimates that over 800,000 crab pots are used annually in NC estuaries.

(legacy.eos.ncsu.edu/eos/info/mea/mea469_info/bluecrab/fishery.html)

|

The primary concern regarding the use of crab pots is the potential navigation hazard they pose when the traps are set and when crab fishers abondon old pots.

(Eggleston, pers. comm. 8/18/03)