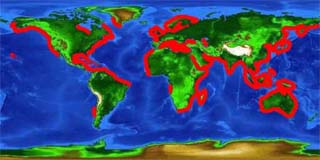

Seagrasses are not "true grasses," but are closely related to lilies. There are approximately 50 different species of marine vegetation considered as seagrass found in temperate and tropical waters worldwide (Figure 1). Seagrasses are found on the bottom of protected bays, lagoons, and other shallow coastal waters, and create a structured habitat in shallow marine and estuarine soft-bottoms. Seagrass habitats harbor dense and diverse assemblages of vertebrates and invertebrates, and provide refuge from predators for juvenile fish and shellfish. Consequently, the role of seagrass beds as nursery habitats are ecologically important.

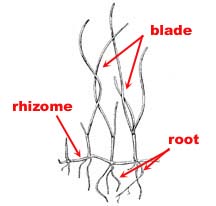

Seagrasses are vascular plants, meaning they have roots. They appear grass-like with shoots of three to five leaf blades attached to a horizontal stem (Figure 2). Some blades can reach several feet above water, and extending rhizomes spread the seagrasses along the shallow coastal water to create large underwater meadows. They are attached to the bottom via thick roots and rhizomes, which enables them to inhabit areas with wave action and strong currents.

(Hovel, 2003; www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/southflorida/seagrass/distribution.html)

|

|

Seagrass beds in North Carolina's estuaries are primarily composed of eelgrass (Zostera marina), shoalgrass (Halodule wrightii), and widgeongrass (Ruppia maritima).

Eelgrass is widely distributed in temperate and subtropical regions. Found along Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida and Pacific coast from Washington to California.

Shoalgrass ranges from North Carolina, south along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts, to the Caribbean. It is also found off of portions of South America, northwestern Africa, Indian Ocean, and the west coast of Mexico.

Widgeongrass is widely distributed in temperate and subtropical regions. Found along the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland south to Texas in North America.

(www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/southflorida/seagrass/Profiles.html)

|

|

|

Waves, currents, and bottom-feeding animals naturally fragment seagrass habitats into patches ranging in size from less than one square meter to thousands of square meters. In addition, boating, fishing, and coastal development are increasingly responsible for seagrass habitat fragmentation.

There is increasing concern regarding survival of organisms that rely on seagrass habitats. Scientists are exploring the extent of impact and juvenile survival from increased patchiness of seagrass habitats due to human activities.

- How are seagrass beds important to blue crabs?

- How can destruction of seagrass beds affect blue crabs?

|

||||||||||||||||||

Many commercially valuable seafood, e.g. blue crab, lobster, pink shrimp, and hard clams, spend a part of their life history in seagrass beds. They rely on seagrass beds for protection from predators, access to food, and to provide a hard surface for the larval or post-larval stage to settle. Post-larval stage of blue crabs migrate into these shallower seagrass beds before metamorphosing into the juvenile stage.

Table 1 shows findings from a study that examined correlations between seagrass habitat fragmentation and juvenile crab survival in North Carolina. Those results reveal that juvenile blue crab survival is influenced by the amount of seagrass cover. More juvenile blue crab survive when there is a higher percentage of seagrass cover. However, survival decreased with more and larger individual seagrass shoots on a particular patch of area. No relationship was found between juvenile survival and actual size of the patch of seagrass habitat or whether there were other patches nearby.

This web site was created by Lynn Tran at the North Carolina State University, Department of Mathematics, Science, and Technology Education on 7/12/03. Faculty advisor Dr. David Eggleston, NCSU, Department of Marine, Earth, & Atmospheric Sciences. Last updated December 29, 2003 .