|

| back

to data |

|

|

|

|

Sea otters

are found from the Gulf of Alaska around the Pacific Rim to northern Japan

with translocated pockets in southern California, Washington, Vancouver,

and southeast Alaska (Figure 1b). It is estimated that 90% of world's

population is found in coastal waters of Alaska.

(biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/s043.htm)

|

|

| Figure

1a. Distribution of sea otters before fur harvest began in 1741

and populations that survived the harvest, providing the nucleus

for recovery of the species. |

|

|

|

|

Figure

1b. Current distribution of sea otters including locations

of successful translocations. Surving otters were used to

initiate translocated populations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

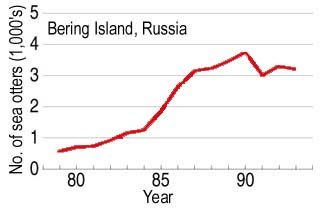

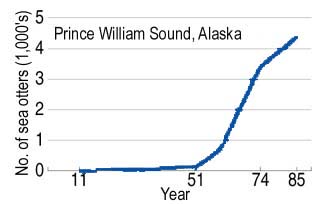

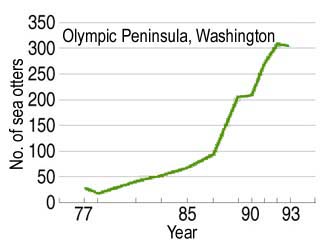

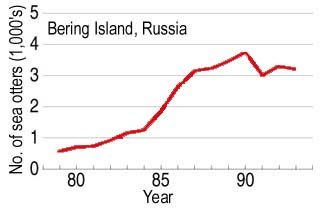

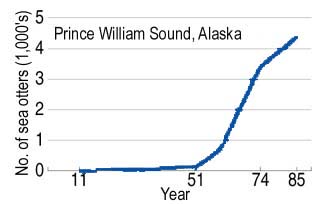

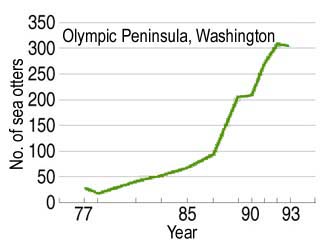

Graphs in Figure

2 show growth patterns observed in three sea otter population stocks in

the north Pacific resulting from natural range expansion.

- Bering Island

was recolonized by growing populations around Medny Island in 1970.

- Sea otters

in Prince William Sound were from the original surviving 1911 population.

- In 1969

& 1970, 59 sea otters were released along the outer coast of Washington

state. This represents a translocated population.

source:

J. L. Bodkin, R. J. Jameson, J. A. Estes (http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/s043.htm)

|

|

|

|

Figure

2. Population growth of sea otters in the Bering Sea, Prince

William Sound, and Olympic Peninsula. |

|

|

|

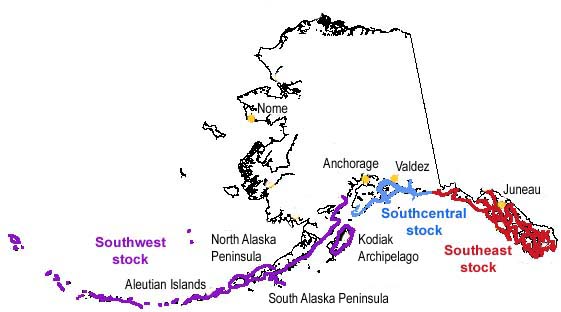

In March 1998,

US FWS officially divided the Alaskan sea otters into three stocks based

on differences in genetics, morphology, and geographic distribution. Figure

3 shows the general location of the three stocks. Recent aerial surveys

suggest:

- translocated

Southeast stock continues to grow

in numbers and expand in range,

- Southcentral

stock

(including Prince William Sound) is either stable or increasing,

- SOUTHWEST

STOCK has declined dramatically in the past 10-15 years

(U.S.

Fish & Wildlife Service, Marine Mammals Management Office, October

2001)

It

is estimated that 90% of the world population of sea otters reside in

the nearshore waters in Alaska. Since the 1911 international fur trade

ban, sea otters have shown healthy recovery. Population growth rates into

unoccupied habitat have been 17-20% per year.

This suggests that something unique is negatively

impacting the Southwest stock since the other stocks continue to prosper.

|

| Table

1. Southwest Alaska sea otter survey results, 1986-2001. |

| Location |

Year |

Count

or Estimate |

Decline |

| Aleutian

Islands |

1992

|

8,044

|

|

|

2000

|

2,442

|

70%

|

| North

Alaska Peninsula |

1986

|

9,061-13,091

|

|

|

2000

|

5,756

|

36-56%

|

|

South

Alaska Peninsula

|

1986

|

15,346-17,835

|

|

|

2001

|

1,344

|

91-92%

|

| Kodiak

Archipelago |

1989

|

13,526

|

|

|

1994

|

9,817

|

|

|

2001

|

5,892

|

56%

|

|

|

|

Table 1 estimates

the percent of population decline between the years indicated for each

location.

-

Could the geographic location of the Southwest stock contribute to the

decline?

|

|

|

|

Figure

3. Map of Alaska indicating general locations of three genetically

distinct sea otter stocks.

|

|

|

|

|

| Table

2 summarizes data from different studies that investigated potential physiological

and behavioral causes for the sea otter decline. The results suggest that

there has not been a reduction in reproduction or a redistribution of sea

otter populations. Exploring the possibilities for increased mortality show

evidence against disease, toxins, and starvation. However, one study provides

strong evidence for increased sea otter predation as a potential cause for

population decline. |

| Table

2. Conclusions from investigations regarding physiological and

behavioral causes for declining sea otter populations |

| Variable

|

Results |

| Reduced

fertility |

Birth

rates of radio-tagged adult females and pup survival at Amchitka

Island (1992-94) and Adak Island (1995-96) were similar to those

of stable populations. |

| Redistribution |

There

has been no population build up on any one island to account

for losses on others. Radio-tagged otters on Amchitka and Adak

show maximum distances moved were 4.31 and 6.95 km, respectively.

Marked animals that were lost disappeared suddenly and without

a trace. |

|

Increased

mortality

|

Population

declines with no reduction in birth rate or evidence of redistribution

suggest increased mortality. Mortality could be caused by disease,

toxins, predation, and starvation. |

|

(Estes

et al, 1998)

|

| Disease |

Few

beach-cast carcasses have been found. Blood analysis of

select otters on Adak, Amchitka, Kiska, and Kanaga Islands

show no signs of diseases. |

| Toxins |

There

have been reports of elevated contaminants in the Aleutian

Island, but they are restricted to a few small areas. |

| Predation |

Although

not a regular part of their diet, there have been at least

10 observed attacks on sea otters by killer whales. Population

comparisons of two sites, Clam Lagoon, Adak Island (inaccessible

to killer whales) and Kuluk Bay (open coastal environment),

from 1993 to 1997 show 76% decline at Kuluk Bay and stable

population at Clam Lagoon. Calculating caloric needs of

killer whale with decline in sea otter population in this

6-year period suggest only 5.05 attacks are needed. Six

of the ten killer whale attacks were observed during this

time period. |

| Starvation |

There

have been increases

in sea urchin biomass during sea otter decline. There

has also been striking changes in the kelp forest ecosystem

accompanying sea otter decline. |

|

|

|

| back

to data |

|

| |

|

This web

site was created by Lynn Tran at the North Carolina State University, Department

of Mathematics, Science, and Technology Education on 7/12/03. Faculty advisor

Dr. David Eggleston, NCSU, Department of Marine, Earth, & Atmospheric Sciences.

Last updated

December 29, 2003

.

|